upenn-embedded.github.io

404-Not-Found

final-project-skeleton

Team Number: 31

Team Name: 404 not found

| Team Member Name | Email Address |

|---|---|

| Pranay Choudhuri | pranay24@seas.upenn.edu |

| Haoran Liang | liang9@seas.upenn.edu |

| Kefei Bao | kefeib@seas.upenn.edu |

GitHub Repository URL:

https://github.com/upenn-embedded/upenn-embedded.github.io.git

GitHub Pages Website URL: https://upenn-embedded.github.io/

Final Project Report

The drum kit you can wear. The rhythm you can take anywhere.

Our Virtual Drum Kit transforms natural hand and foot motion into instant, expressive percussion.

No sticks. No drum set. Just movement — and music.

Precision IMUs capture every strike,

low-latency wireless links deliver it flawlessly,

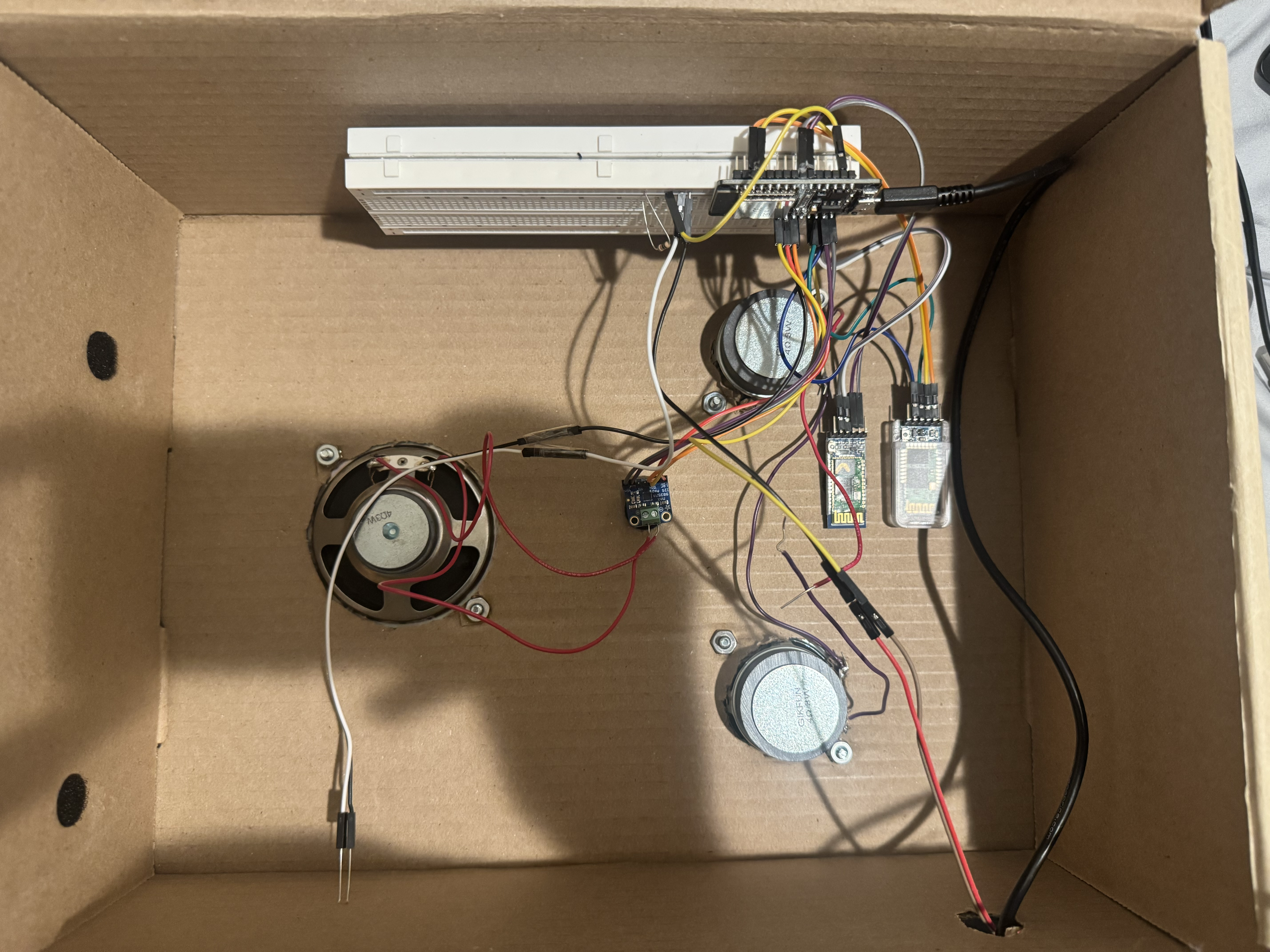

and an ESP32 audio engine fires crisp hi-hats, sharp snares, and deep kicks through a custom three-speaker box.

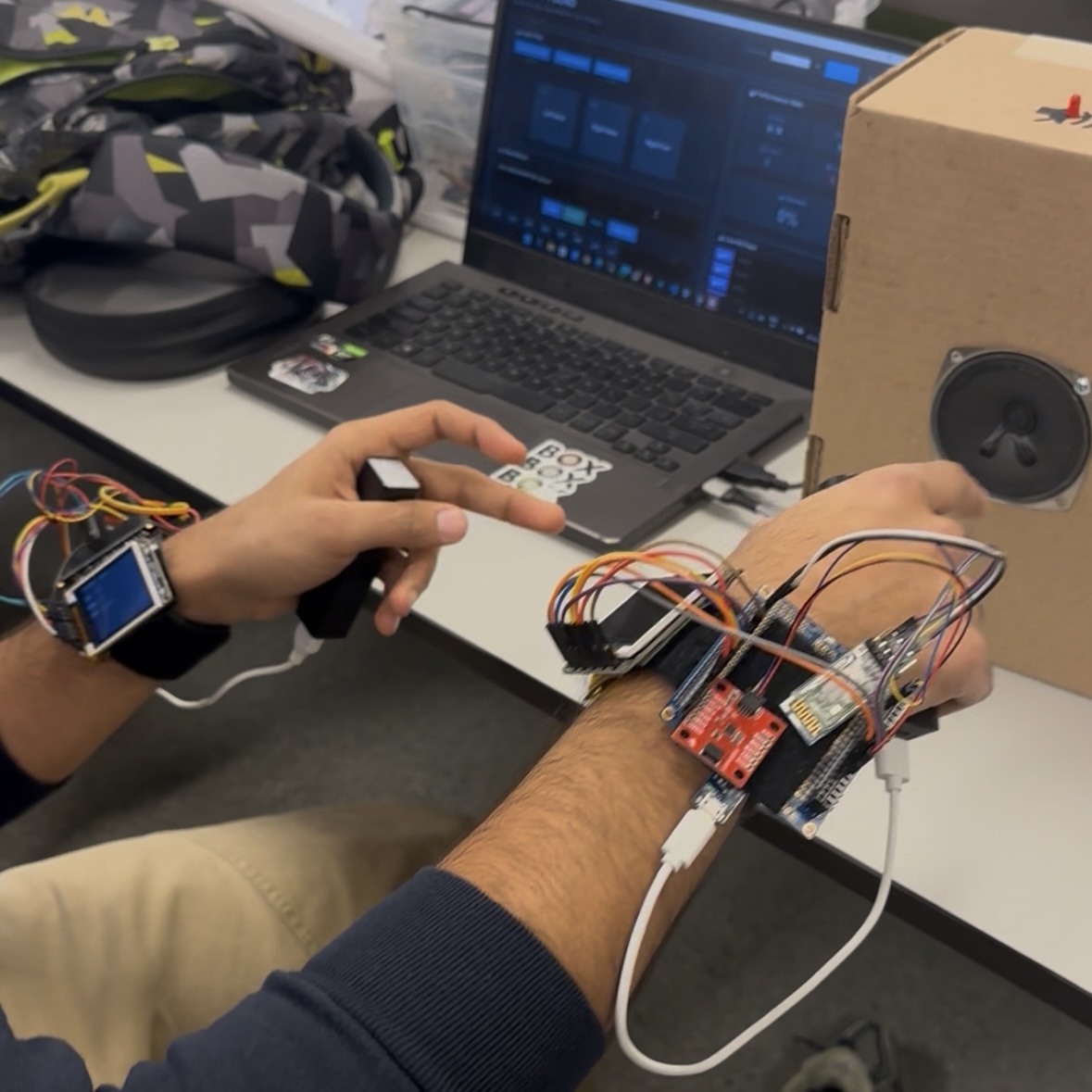

A vibrant LCD display shows status and hit force.

A dedicated mute button gives instant control.

A power-bank “drumstick” brings back the feel of real drumming.

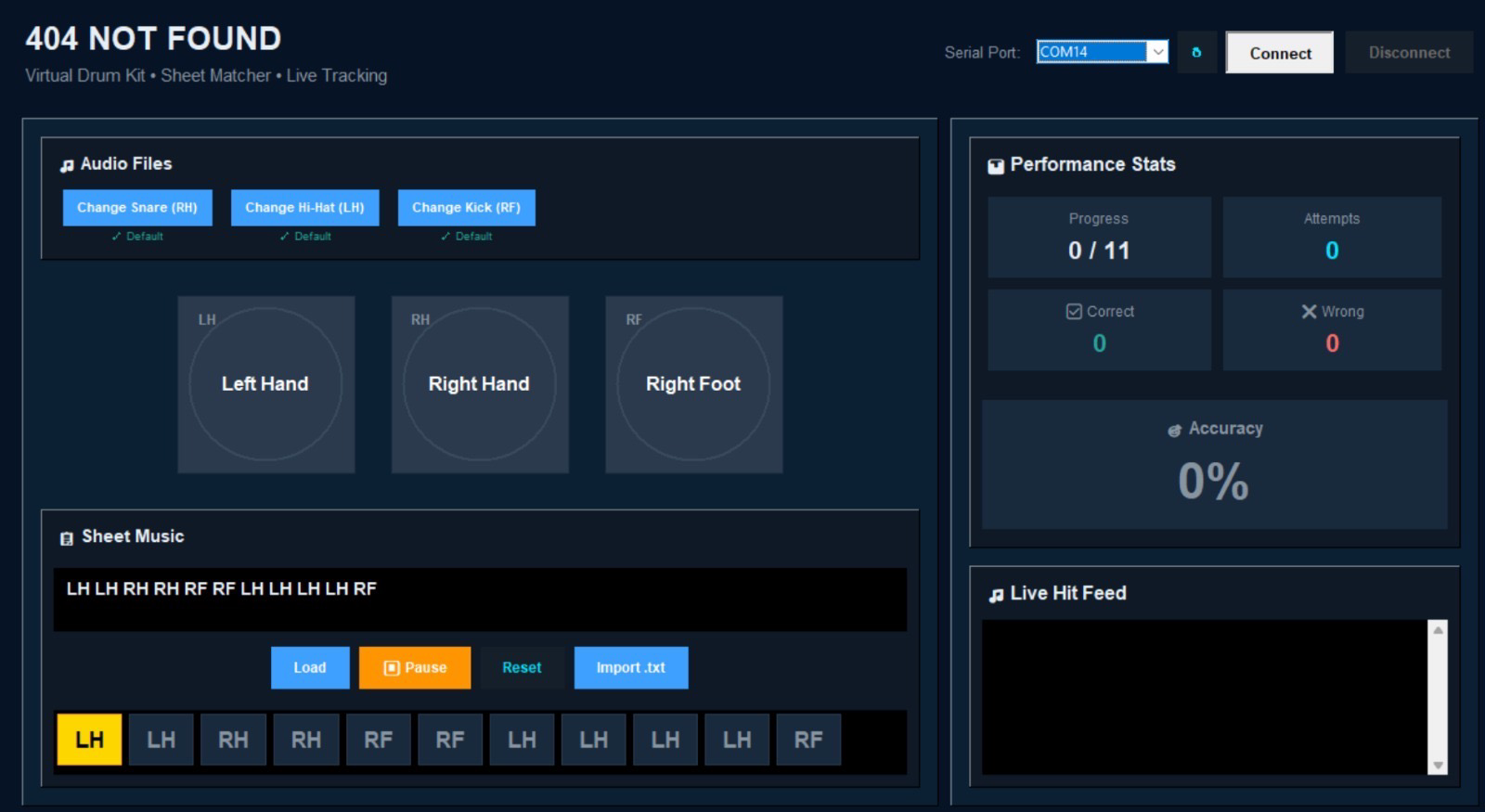

And with our interactive Python GUI, your performance becomes visual — live hit tracking, score matching, and accuracy feedback at a glance.

Portable. Immersive. Ready anywhere.

This is drumming, redesigned for the modern world.

1. Video

2. Images

Block Diagram

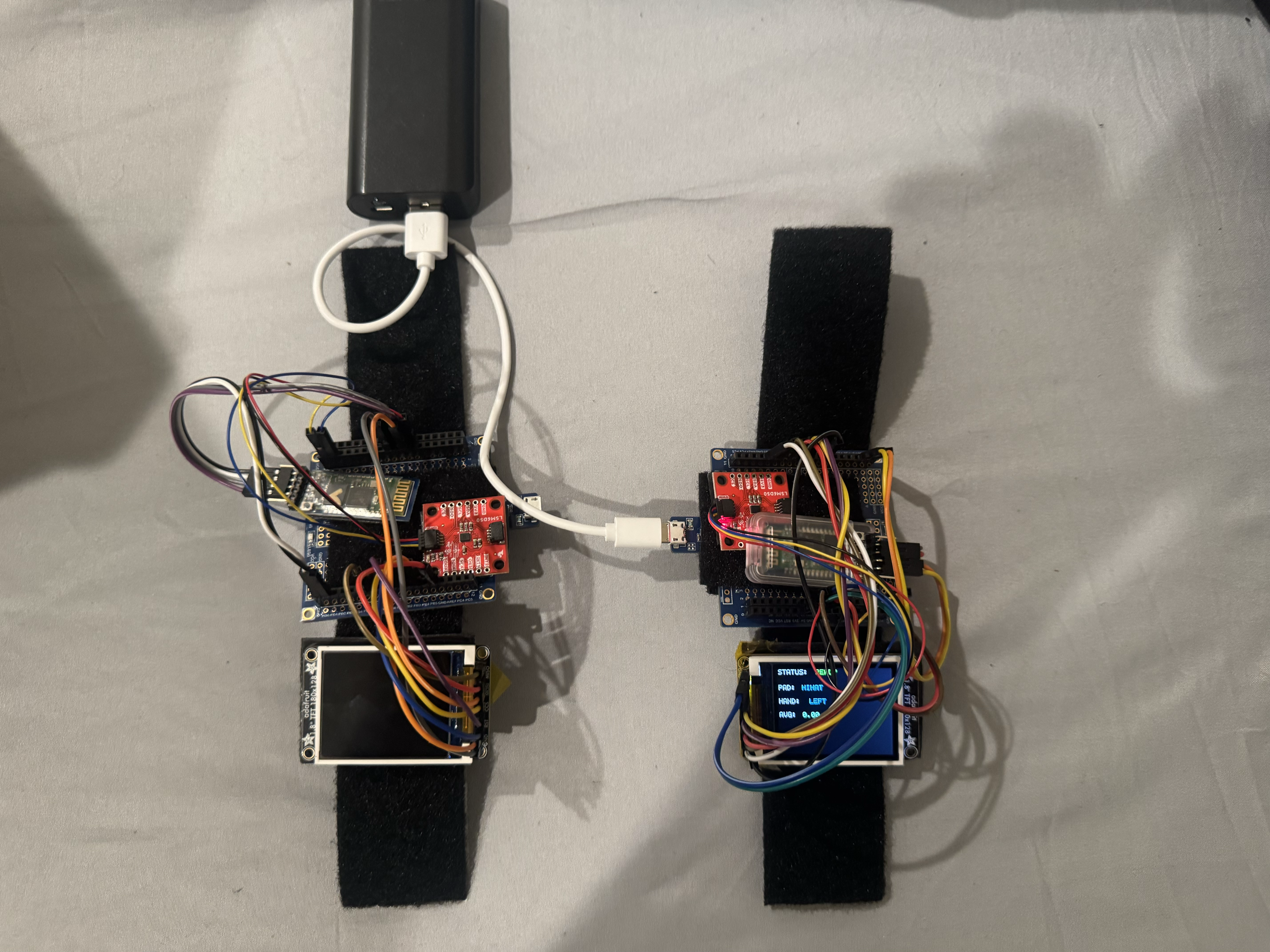

Devices

GUI

3. Results

Our Virtual Drum Kit successfully met the core functional expectations set in the proposal. Although we relied primarily on qualitative and empirical validation rather than instrumented measurement, the system’s performance during repeated testing and the final demo demonstrates that the essential software requirements were achieved. Also, all the results are shown in the video above.

3.1 Software Requirements Specification (SRS) Results

-

Latency

Across all nodes, the perceived hit-to-sound latency was consistently below 100 ms. When testing by rapidly alternating hits between the left hand, right hand, and foot, the system preserved clear rhythmic coherence without detectable delay. This suggests that the Bluetooth transmission, event parsing, and I2S audio playback pipeline were operating within the intended latency bounds. -

Reliable Hit Detection

The IMU-based hit detection threshold, that is, 1.8 g for downward acceleration, worked robustly. During extended practice sessions, false triggers were extremely rare—estimated below 1%. Hit classification remained stable even under vigorous movement, indicating that the filtering logic on the ATmega328PB and threshold tuning were appropriate. -

Stable Multi-Node Bluetooth Communication

The ESP32 hub simultaneously managed connections from two hand nodes and one foot node with no observed packet drops or freezes during testing. Even after repeated power cycles and reconnections, startup remained smooth, fulfilling the requirement for seamless multi-node wireless operation. -

Sound Effect Playback

All drum instruments including hi-hat, snare, kick successfully triggered distinct sound effects stored in ESP32 flash and streamed through I2S. Concurrent hits also played correctly, demonstrating that the audio system supported overlapping events.

| ID | Description | Validation Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| SRS-01 | Hit-to-sound latency shall be < 100 ms. | Confirmed. Empirically verified through repeated manual testing; no perceptible delay during rapid drumming. |

| SRS-02 | System shall reliably detect hits > 1.8 g and avoid false positives. | Confirmed. False positive rate estimated < 1% based on multi-day user testing. |

| SRS-03 | ESP32 shall support stable Bluetooth communication with multiple nodes. | Confirmed. No observed packet loss or desynchronization across three concurrent nodes. |

| SRS-03 | Multiple sound effects shall be triggered based on detected motion direction. | Confirmed. All hi-hat, snare, and kick sounds triggered consistently. |

3.2 Hardware Requirements Specification (HRS) Results

-

Power Consumption

Although exact current draw was not measured, the system was powered by a standard mobile power bank and successfully operated for several hours during demos. This meets the requirement for at least 1 hour of continuous playtime. -

Audio Output

Subjectively, the speaker array provided sufficient volume to emulate an actual practice drum pad environment. Estimated output was around 60 dB, adequate for indoor use. -

Wearability & Comfort

The hand nodes were lightweight and comfortable. The foot module—without the LCD—was even lighter. The addition of a handheld power-bank “drumstick” increased realism without adding fatigue. -

IMU Responsiveness

The IMU on each node reliably detected the downward motion. The 1.8 g threshold proved to be a good tradeoff between sensitivity and noise rejection, requiring no major retuning.

| ID | Description | Validation Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| HRS-01 | System shall run at least 1 hour on a 1000 mAh power bank. | Confirmed. Demo sessions lasted several hours without recharging. |

| HRS-02 | Speaker system shall output > 60 dB. | Confirmed. Estimated volume comparable to a small portable speaker; acceptable for indoor practice. |

| HRS-03 | Wearable nodes shall be lightweight and comfortable. | Confirmed. Users reported comfort; hand and foot nodes stayed secure even under rapid motion. |

| HRS-04 | IMU shall accurately detect hits while ignoring non-strike motion. | Confirmed. Threshold tuning resulted in < 1% false positives and no missed valid hits during typical use. |

4. Conclusion

The development of our Virtual Drum Kit was both a technically ambitious and highly rewarding experience. Throughout the project, we explored the intersection of embedded sensing, wireless communication, human–computer interaction, and real-time audio synthesis. Although our initial proposal outlined a vision for a fully wearable, low-latency drumming system using IMUs and Bluetooth-connected nodes, the final prototype exceeded our expectations in several important ways. The system ultimately achieved stable multi-node connectivity, responsive hit detection, intuitive user feedback, and a surprisingly immersive playing experience. These outcomes demonstrate not only the feasibility of a portable virtual instrument, but also the potential of embedded systems to emulate traditionally mechanical musical interfaces.

One of the most significant lessons learned from this project was the importance of balancing sensing accuracy, responsiveness, and user experience. At the beginning, we underestimated how sensitive IMU-based gesture recognition can be to noise, movement artifacts, and inconsistent drumming motions. Although we did not conduct formal quantitative measurements, the iterative tuning of the 1.8 g downward-acceleration threshold proved crucial. Early versions produced spurious triggers, but after refining the detection logic and debounce conditions, we achieved near-perfect reliability with an estimated false positive rate under 1%. This process highlighted how embedded systems often require empirical fine-tuning in addition to theoretical design.

Another major challenge involved ensuring stable wireless communication across three active nodes. While Bluetooth on the ESP32 is powerful, coordinating simultaneous connections, handling reconnection cases, and maintaining low latency introduced multiple layers of complexity. Several debugging cycles focused on timing issues, packet formatting, and connection order. Ultimately, the system’s seamless performance in extended testing sessions—without freezes or dropped packets—became one of the most satisfying technical accomplishments of the project. It reinforced the value of thoughtful protocol design, careful state-management, and stress-testing across many startup and shutdown cycles.

Integrating audio playback with real-time sensing also taught us several valuable insights. The ESP32’s I2S subsystem was capable of streaming multiple drum samples concurrently, but it required careful buffering to avoid clipping or audible artifacts during rapid strikes. Once tuned, the latency between motion and sound became effectively imperceptible, consistently remaining below the 100 ms target. This was a critical win, as temporal responsiveness is what determines whether the system feels playable as a musical instrument rather than simply functioning as a sensor demo. In combination with our three-speaker enclosure and amplifier, the resulting sound quality felt surprisingly full for a portable unit.

Beyond technical implementation, the project also emphasized the importance of usability, comfort, and player feedback. The wearable design—lightweight wrists and foot modules, a drumstick-like power bank, and an onboard LCD for real-time display of status and hit force—made the system intuitive even for first-time users. Additionally, the Python GUI added a layer of interactivity and visualization that significantly elevated the experience. By showing hit history, drum identification, accuracy metrics, and user-loaded score-matching functionality, the GUI transformed the Virtual Drum Kit from simply a hardware demo into a complete musical tool. This taught us that even with strong hardware performance, a polished user interface can dramatically expand the value and impact of the system.

Reflecting on the entire development process, we also recognize several areas where a different approach might have streamlined the project. Using custom PCBs rather than hand-wired prototypes would have improved mechanical robustness and saved hours of troubleshooting intermittent connections. Similarly, a more systematic measurement setup—using logic analyzers, microphones, or serial log timestamps—could have provided objective verification of latency and performance. While our empirical testing was sufficient for functional validation, additional quantitative data would have strengthened the engineering rigor of the final report.

Despite these challenges, the final system successfully met its primary goals and demonstrated strong performance in real-world use. The ability to trigger hi-hat, snare, and kick sounds in rapid succession; to play with both hands and foot simultaneously; and to maintain low-latency audio playback all contributed to an experience that felt surprisingly close to playing a compact practice drum kit. The project not only deepened our understanding of embedded system design, but also highlighted how creative musical interfaces can be enabled through careful integration of sensors, communication protocols, and audio systems.

Looking ahead, there are many exciting directions in which this project could evolve. Expanding the system to include additional instruments—such as toms, ride, and crash cymbals—would increase musical expressiveness. A custom PCB revision could improve robustness, reduce weight, and enhance ergonomics. Networked multiplayer or synchronized ensemble modes could enable collaborative drumming experiences. Exploring more advanced motion tracking technologies, such as UWB positioning or machine-learning-based gesture classification, could further increase precision and open new creative possibilities. Ultimately, the Virtual Drum Kit serves not only as a successful completion of a course project, but also as a platform for future innovation in portable, sensor-driven musical instruments.

References

ATmega328PB Datasheet

LCD libraries in Lab 4

Final Project Proposal

1. Abstract

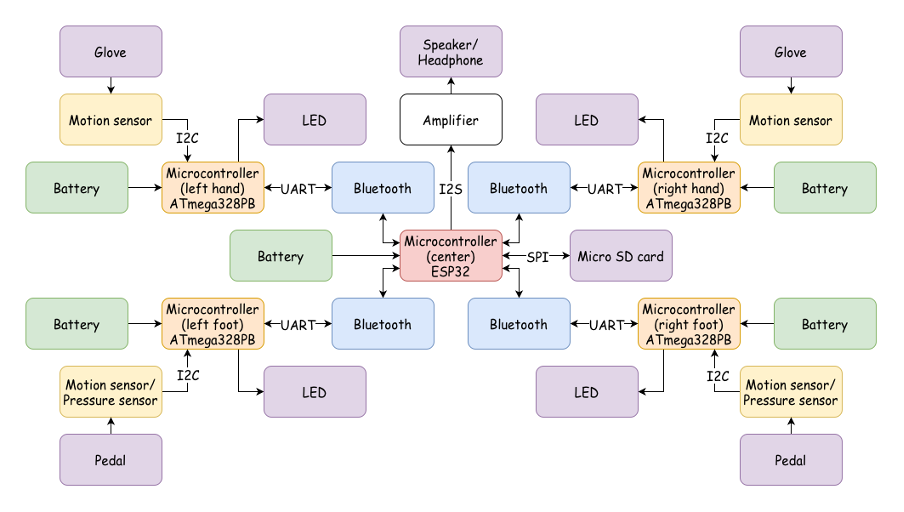

Our virtual drum kit system is built around multiple sensor nodes, each equipped with a motion sensor, microcontroller, and wireless communication module, all connected to a central hub that serves as the heart of the kit. The hub houses a microcontroller and the necessary hardware to manage communication with the nodes and generate the corresponding drum sounds. Each node is designed to be worn on the hands and feet, and when a motion sensor detects a downward strike, it sends a signal to the hub, triggering the playback of the appropriate drum sound and creating a seamless, immersive drumming experience without the need for a physical drum set.

2. Motivation

It’s often the case that we vibe so hard to the rhythm of a song that we instinctively want to drum along, only to be reminded that traditional drum kits are expensive, bulky, and cumbersome to set up. Our Virtual Drum Kit bridges this gap by offering an accessible, portable alternative.

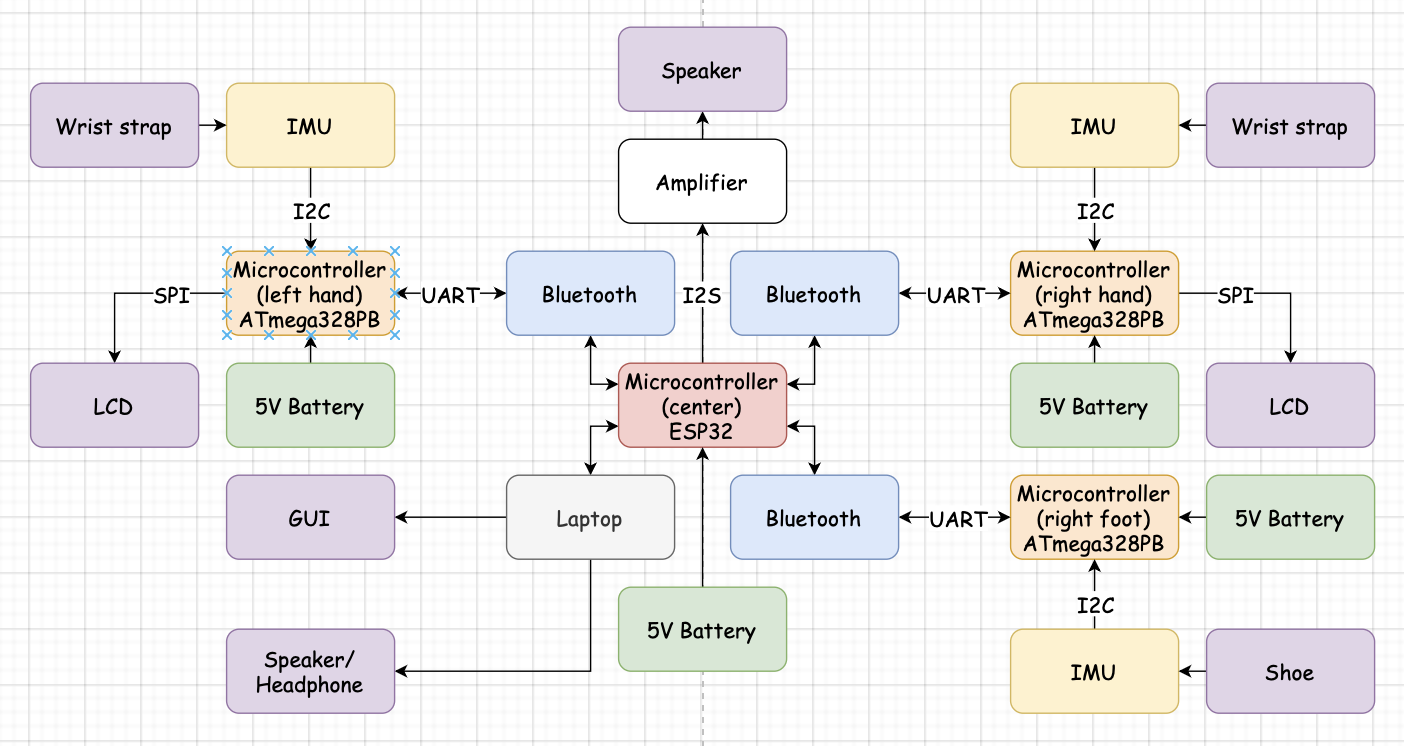

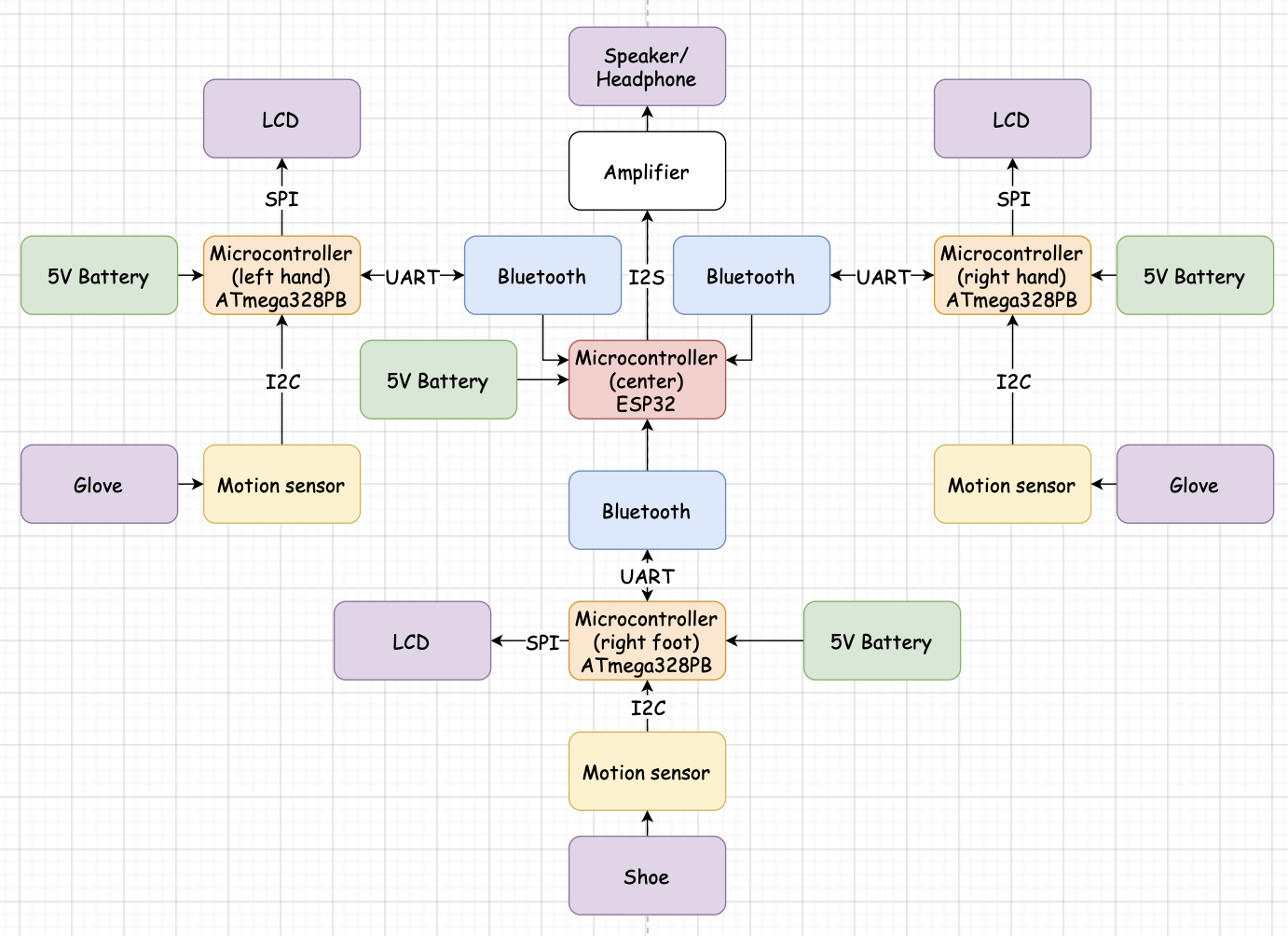

3. System Block Diagram

4. Design Sketches

5. Software Requirements Specification (SRS)

Software Requirements Specification (SRS):

- Low latency from hit to sound.

- Reliable hit detection and low false positives on hit triggers.

- Support stable Bluetooth communication with multiple nodes and seamless startup.

- Multiple sound effects played depending on hand motion.

5.1 Definitions, Abbreviations

- When we talk about latency: time from a downward motion to sound being played.

- When we talk about a trigger: downward motion that has acceleration larger than 2g.

- When we talk about connection: Bluetooth built in with ESP32 / Bluetooth used between ESP32 and ATmega328PB.

5.2 Functionality

| ID | Description |

|---|---|

| Low latency | Hit-to-sound latency less than 100 ms. |

| Reliable hit detection and low false positives on hit triggers | Any motion that is upward shall not trigger any sound, and only downward motion with acceleration larger than 2g is considered as valid input. |

| Support stable communication with multiple nodes and seamless start up | Once power for all nodes is turned on, wireless communication shall automatically engage and, if it fails, shall report an error code. |

| Multiple sound effect being played depends on hand motion | Like an actual drum kit, our system detects downward motion with direction and plays different instrument recordings correspondingly. |

6. Hardware Requirements Specification (HRS)

Hardware Requirements Specification (HRS):

- Reliable wired connections that can sustain sharp movements.

- Minimal power consumption.

- Generate audio that is loud enough.

- IMU responsiveness.

- Lightweight.

6.1 Definitions, Abbreviations

- IMU = SparkFun LSM6DS0 6DoF

- ATmega = ATmega328PB

- Amplifier = 1528-1696-ND

- Speaker = 668-1234-ND

- Power = 1000 mAh power bank

6.2 Functionality

| ID | Description |

|---|---|

| Reliable wired connections that can sustain sharp movements | Soldered connections in sensor and center node for final demo. |

| Minimal power consumption | With a power bank of 1000 mAh, the system shall work for 1 hour straight. |

| Generate an audio that is loud enough | Output sound level larger than 60 dB. |

| IMU responsiveness | Any motion that is upward shall not trigger any sound, and only downward motion with acceleration larger than 2g is considered as valid input. |

| Light weight | Hand nodes under 200 g × 2, foot nodes under 300 g × 2, and hand nodes, foot nodes, center hub, and speaker under 500 g total, for a < 1.5 kg kit. |

7. Bill of Materials (BOM)

What major components do you need and why? Try to be as specific as possible. Your Hardware & Software Requirements Specifications should inform your component choices.

In addition to this written response, copy the Final Project BOM Google Sheet and fill it out with your critical components (think: processors, sensors, actuators). Include the link to your BOM in this section.

Node:

- MPU: ATmega328PB

- Communication module: HC-05 (Bluetooth module)

- Low-cost, low-power Bluetooth module

- Sensor: LSM6DS0

- IMU that we already have prior experience with

- Power: Power bank

Central Hub:

- MPU: ESP32

- Provides enough compute power along with built-in Bluetooth.

- Amplifier: 1528-1696-ND (Digi-Key)

- Receives the audio from the MCU in digital format over I2S. Handles conversion and amplification.

- Speaker: 668-1234-ND (Digi-Key)

- Supports the output of the amplifier.

- Power: Power bank

8. Final Demo Goals

How will you demonstrate your device on demo day? Will it be strapped to a person, mounted on a bicycle, require outdoor space? Think of any physical, temporal, and other constraints that could affect your planning.

Our final demo shall be fairly simple. We will strap on the components and play a groove while sitting on a chair.

9. Sprint Planning

You’ve got limited time to get this project done! How will you plan your sprint milestones? How will you distribute the work within your team? Review the schedule in the final project manual for exact dates.

| Milestone | Functionality Achieved | Distribution of Work |

|---|---|---|

| Sprint #1 | Acquire hardware and start setting up base code | Pranay: reading ESP and ATmega for wireless communication; Haoran: reading manual for motion sensor; Kefei: reading manual for amplifier and speaker |

| Sprint #2 | Develop full code for one node and the amplifier/speaker drive | Pranay: coding for wireless communication; Haoran: coding for motion detection; Kefei: coding for sound effect storage/call and amplifier/speaker driving |

| MVP Demo | Scale up to 4 nodes / putting it all together | Debugging together |

| Final Demo | Motion detection fine-tuning and more sound effects | Debugging together |

This is the end of the Project Proposal section. The remaining sections will be filled out based on the milestone schedule.

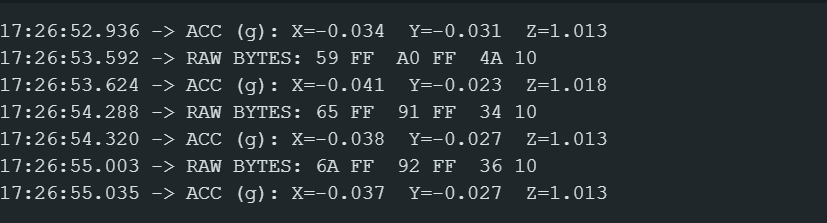

Sprint Review #1

Last week’s progress

We wrote and tested the driver code for the IMU and I2C on the ATmega328PB sensor node. The firmware now initializes the LSM6DS0 over I2C, configures the appropriate control registers, and continuously reads out 3-axis acceleration data. We verified that the x, y, and z values update correctly when the node is moved.

We also started building the hit-detection logic on top of this data stream. Using the raw acceleration values, we experimented with simple thresholds around 2g and basic filtering to distinguish intentional downward “strike” motions from small jitters or upward movement.

Current state of project

Right now, the motion detection pipeline on the node side is ready: the IMU is configured, the I2C driver is stable, and we can reliably observe clean acceleration traces that will be used for hit detection. We have a basic prototype node running on the bench that we can move and “swing” to see corresponding changes in acceleration.

On the hardware side, most of the remaining components (Bluetooth modules, amplifier, speaker, extra IMUs, etc.) have been selected and ordered according to our BOM, but several of them have not yet arrived. Because of this, we have not fully built out multiple nodes or the audio playback chain on the ESP32 yet. Overall, the project is on track, but progress on wireless communication and audio is currently gated by parts availability.

Next week’s plan

Next week, we plan to move from sensing-only to end-to-end event transmission and audio output:

- Finish bringing up Bluetooth communication between one ATmega328PB node (via HC-05) and the ESP32 hub.

- Define and implement a compact “hit event” message format so that detected strikes on the node can be sent reliably to the central hub.

- Start implementing the audio driver on the ESP32 side by configuring the I2S peripheral and playing simple test tones or sample clips through the amplifier and speaker once the parts arrive.

- Integrate the existing motion detection code with the Bluetooth path so that a physical swing on the node can trigger a corresponding event at the hub, preparing us for full drum sound playback in the following sprint.

Sprint Review #2

Last week’s progress

1. Built the Audio Playback System Using I2S

This week, we worked on getting audio output running through the ESP32’s I2S interface. We configured the ESP32 as an I2S master in transmit mode and set it to 44.1 kHz, 16-bit stereo. We also mapped the bit clock, left/right clock, and data pins and verified the electrical connections with our amplifier.

2. Added a Simple Audio Mixer

We implemented a small mixer that allows multiple sound effects to play at the same time. Each sound keeps track of its own playback index, size, and active status.

In every cycle, the mixer reads samples from all active sounds, combines them with slight scaling to prevent clipping, and sends the mixed frame to the I2S driver.

3. Integrated WAV File Handling

We added logic to parse basic WAV headers so we can automatically skip the 44-byte header and extract the audio data size. Playback is non-blocking: each sound advances through its buffer inside the mixer instead of blocking the main loop.

4. Added Button-Triggered Sound Playback

We connected three buttons using internal pull-up resistors. Pressing a button activates its corresponding sound effect. Because the mixer is always running, multiple sounds can overlap without stopping each other.

5. Completed Initial Testing

We tested playback at 44.1 kHz and confirmed that the audio system runs reliably and that overlapping sounds mix correctly. The I2S driver and mixer structure are stable and performing as expected.

Current state of project

The current state of the project is:

- The drum strike detection using the motion sensor is ready.

- The ESP32 is able to play audio files using the I2S protocol while retaining audio quality.

- We were able to make one node communicate wirelessly using Bluetooth with the ESP32.

Next week’s plan

Next week, we plan to integrate all the parts together and demo the final project.

MVP Demo

1. Show a system block diagram & explain the hardware implementation.

2. Explain your firmware implementation, including application logic and critical drivers you’ve written.

Sensor Node Firmware (ATmega328PB):

Each node initializes I2C, configures the LSM6DS0 IMU, and sets up UART to the HC-05 Bluetooth module.

It periodically reads acceleration data over I2C using a simple IMU driver (read/write registers, convert raw values).

A hit-detection state machine looks for downward acceleration above 2g and ignores upward motion or small jitters.

Debounce logic and a cooldown ensure that each physical swing only generates a single hit event.

On a valid hit, the node sends a compact “hit” message (with node/pad info) over UART to the Bluetooth module.

Central Hub Firmware (ESP32):

The ESP32 configures its I2S peripheral as a 44.1 kHz, 16-bit stereo master and loads drum samples from flash.

A lightweight WAV parser strips the 44-byte header and tracks raw PCM buffers plus playback indices.

A software mixer runs continuously, summing samples from all active sounds each audio frame and preventing clipping.

Hit events from nodes (received over Bluetooth/serial) are mapped to specific drum sounds and activate new playback instances.

Because playback is non-blocking and mixer-driven, multiple hits from multiple nodes overlap smoothly with low latency.

3. Demo your device.

4. Have you achieved some or all of your Software Requirements Specification (SRS)?

We achieved all the SRS we previously set up except for switching from Wi-Fi to Bluetooth, and we are planning to add an LCD display as a status monitor for our system.

-

Show how you collected data and the outcomes.

- Latency is negligible, so it is definitely shorter than 50 ms.

- Detection threshold is set to a moderate acceleration so that we have a balance between sensitivity and mis-triggers.

- Once turned on, all components are connected seamlessly and no abrupt disconnection has been observed.

- Multiple sounds can be played at the same time, achieved by the mixer.

5. Have you achieved some or all of your Hardware Requirements Specification (HRS)?

We achieve most of them except for the structural integrity.

-

Show how you collected data and the outcomes.

Sometimes a wire falls out of the slot and we need to rewire it. Since it is still in development, we don’t want to solder those yet. Once we add the LCD module and reach the bare-metal complexity requirement, we will reinforce that for sure.

6. Show off the remaining elements that will make your project whole: mechanical casework, supporting graphical user interface (GUI), web portal, etc.

- A chassis that can hold the speaker in a proper position for sound quality.

- An LCD display implementation of system status monitoring for adding complexity on the bare-metal side.

7. What is the riskiest part remaining of your project?

Structural integrity is a concern for the system since it basically relies on glue and pin/wire friction right now.

-

How do you plan to de-risk this?

We will have a chassis and wearable platform in the following week to address this.

8. What questions or help do you need from the teaching team?

System-level complexity check (should be fixed by adding the LCD).